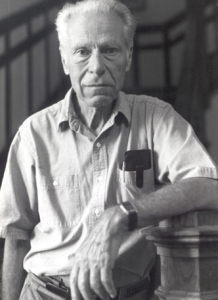

I’ve long-admired the writings of economist and public intellectual Albert O. Hirschman, who died a few months ago at 97. In addition to his ideas, he had a remarkable, little publicized and heroic life during World War II, as this New York Times obituary reveals. And this essay by Roger Lowenstein in the Wall Street Journal shows how Hirschman offered some interesting perspectives about the role of dissent, relevant to politics and organizations. Lowenstein writes, “Once you start looking at the world through the Hirschman lens, the paradigm of exit and voice is all around. Suppose you are unhappy at work: Should you complain to the boss or simply quit? Or maybe you are the boss: How much should you mollify employees—or customers—to keep them from leaving? It might depend on the presence of a third Hirschman factor: loyalty. Broadly speaking, markets are all about exit, while politics deals in voice. What Hirschman grasped is that the strongest organizations (in either sphere) foster exit as well as voice.”

I’ve long-admired the writings of economist and public intellectual Albert O. Hirschman, who died a few months ago at 97. In addition to his ideas, he had a remarkable, little publicized and heroic life during World War II, as this New York Times obituary reveals. And this essay by Roger Lowenstein in the Wall Street Journal shows how Hirschman offered some interesting perspectives about the role of dissent, relevant to politics and organizations. Lowenstein writes, “Once you start looking at the world through the Hirschman lens, the paradigm of exit and voice is all around. Suppose you are unhappy at work: Should you complain to the boss or simply quit? Or maybe you are the boss: How much should you mollify employees—or customers—to keep them from leaving? It might depend on the presence of a third Hirschman factor: loyalty. Broadly speaking, markets are all about exit, while politics deals in voice. What Hirschman grasped is that the strongest organizations (in either sphere) foster exit as well as voice.”

The complete essay:

Four decades ago, an economist named Albert O. Hirschman prophesied a rising gap in the quality of schools. As he reasoned: If the quality of public schools deteriorated, affluent families would switch to private schools. Hirschman labeled this the “exit” option. The parents of the remaining kids would try to restore quality via “voice”—that is, by appearing at school board meetings, speaking out, writing letters. But these activists would be doubly handicapped. Public schools—being insensitive to profit—are less responsive to voice. And the desertion of wealthier parents would tend to deprive the public schools of influential voices.

Once you start looking at the world through the Hirschman lens, the paradigm of exit and voice is all around. Suppose you are unhappy at work: Should you complain to the boss or simply quit? Or maybe you are the boss: How much should you mollify employees—or customers—to keep them from leaving? It might depend on the presence of a third Hirschman factor: loyalty.

Broadly speaking, markets are all about exit: If the stock is a lemon, sell it. Politics deals in voice (just listen to talk radio).

What Hirschman grasped is that the strongest organizations (in either sphere) foster exit as well as voice. Both corporations and school districts have customers or members whom they need to retain—though at some point, it’s best to let the dissenters go.

Hirschman died late last year, at 97, and a massive, erudite biography by Jeremy Adelman will be published next month. “Worldly Philosopher: The Odyssey of Albert O. Hirschman” (Princeton University Press) chronicles the amazing saga that brought him from the caldron of Hitler’s Germany to a revered place in American letters. “Interestingly,” Mr. Adelman tells us, “Hirschman made no mention of his own exits—Berlin, Trieste, Paris.”

Perhaps he didn’t have to. When Hirschman wrote “Exit, Voice and Loyalty”—a 126-page burst of lucidity—in 1970, its relevance was stunningly apparent. Organizations were in disrepair. The government and campuses had been rocked by Vietnam; big corporations were on the defensive. Which tactic, Hirschman wondered, produced the greater effect: protesting the draft or fleeing to Canada? To whom did the ailing General Motors listen: the silent customers defecting to Toyota or Ralph Nader, the vocal activist?

Born in 1915 in wartime Berlin, Hirschman was reared in a Weimar Germany that was a hotbed of the avant-garde—modernity in culture and radicalism in politics. By the eve of his 18th birthday, the Reichstag had been reduced to ashes, as had his family’s belief that assimilation as Germans immunized them as Jews. The adolescent Hirschman decamped solo for Paris, acquiring a personal resilience that would inform his masterwork. For the rest of his life he would renounce extremes. In his biographer’s piquant phrase, Hirschman dwelled “in the neglected, ravaged space between the romance of revolution and the firmament of reaction.”

If “Exit, Voice and Loyalty” had a broader purpose, it was to make organizations more resilient. Economists, Hirschman noted, didn’t worry about organizational decline; in the economist’s neat models, a bankrupt firm was replaced by another. For Hirschman, upheaval was more frightening. By the time he was 30, he had fought against Franco in Spain, served as a courier for the anti-Mussolini underground in Trieste, enlisted in the French army, and fled to Spain over the Pyrenees and then to America. Having lived history at warp speed, he was done with cosmic doctrines. He preferred the moralism of Albert Camus, the pragmatism of Adam Smith.

“Exit, Voice and Loyalty,” which still inspires Hirschman groupies, grew from one of his beloved “small ideas,” his observation that the poor performance of the railroads in Nigeria did not inspire a clamor for reform. The most disgruntled freight customers defected to private truckers, and their voices were thus lost. More recently, had it not been for Federal Express, sopping up the customers with the most urgent business, the post office probably would have faced a mass riot. Recognizing this truth, totalitarian regimes such as Cuba have preferred to weaken the potential for unrest by tolerating some emigration (exit).

Hirschman saw that when organizations make it easy to exit, voice is weakened. Yet, for voice to be effective, a possibility of exit must be present. Partners in business—even in marriage—trade in voice, but the unstated potential for exit, no matter how remote, gives their requests (“Empty the garbage, please”) particular urgency. Exit and voice coexist in “seesaw,” as Hirschman wrote, but their effects are distinct. When you say to the waitress, “The hamburger is overcooked,” your message is clear, though the waitress may choose to ignore it. If you stop patronizing the restaurant, the meaning is less certain. Were you driven off by the hamburger or something else altogether?

Exit is forceful, but it rules out using voice later. However, the reverse isn’t true. Voice, the default tactic in social groupings, is reusable but messy and not necessarily persuasive. When it’s easy to bid adieu (say, to a brand of detergent), voice isn’t worth the trouble. Firms must rely on the third leg of Hirschman’s stool, “loyalty.” Or as he put it, “Loyalty holds exit at bay”—a truth not lost on the folks who conjured up airline frequent-flier miles.

Loyalty carries no weight, of course, in the stock market, where “exit strategy” is an honored term. And since the appearance of “Exit, Voice and Loyalty” more than four decades ago, financial markets and American culture generally have only become more fickle. Loyalty to geography, religion and firm struggles with the pace of modernity. Professional sports are less appealing because players desert their teams; pensions have fallen into disregard because corporations, which once prized their workers’ loyalty, now value their exit more. And the Internet enforces an exit bias: Habits of behavior and even “friends” are dispatched at a keystroke.

What would Hirschman say today? His biographer writes that he “neither touted the exit-market option nor the voice-political one.” Yet Hirschman was an economist, and his first concern, one suspects, was his colleagues’ neglect of the power of voice. He skewered Milton Friedman for writing that parents can “express” their views about schools “directly”—by switching schools—or through “cumbrous political channels.”

But what was “cumbrous” about voice? A noneconomist, he noted dryly, “might naively suggest that the direct way of expressing views is to express them!” Hirschman also chided political scientists for neglecting exit.

But 2013 is not 1970. The world has moved on, has embraced markets more and social adhesiveness less. So perhaps it is time for some balance, for social structures that listen better and slow the impulse to quit. To paraphrase a cry from the decade that sparked Hirschman’s remarkable book, we should give voice—lest it atrophy—a chance.